Santo Cristo Chapel

The chapel of Santo Cristo de la Vega owes its current reform to the early 18th century, when the main chapel (1701-1703) and the choir (1716-1719) were built. We know that it was given to the Dominican Order in 1599, and was then a humble chapel with an adjoining house. Prior Fray Tomas Gómez gave it a major boost in between 1632 and 1640.

The most important pieces in the church are the Virgen de la Vega, the oldest artefact in Albarracín, from the 12th century. It is a seated Virgin, which is currently missing the Baby Jesus that was to her left. The other object is the Santo Cristo de la Vega, which we will describe later. Treasures from the old chapel include a 16th-century canvas of Ecce Homo with a notable Flemish influence. Also, the 17th-century altarpiece of La Dolorosa, and from the same period, the painting of the Holy Family and the decoration of the pulpit. The chapel was restored again in 1983, returning its luminosity and 18th-century dome.

Devotion

Devotion to the Santo Cristo de la Vega dates back to Mozarabic times. There are indications that it was already venerated in the times of the Azagras, when the primitive chapel was located in the same place and dedicated to the Virgen de la Vega, and in which there was also a chapel dedicated to the Santo Cristo de la Vega, known formerly as ‘el Abuelo’ (the grandfather) as a reference to his age and familiar tenderness.

A centuries-old tradition takes place on 14 September during the festivities of the Patron Saint of Albarracín, when there is a pilgrimage in honour of the Santo Cristo de la Vega attended by inhabitants of the Sierra de Albarracín and the surrounding area. In fact, this chapel is considered a sanctuary to which people from many towns and villages made a pilgrimage on other dates to pray for the intervention of the Santo Cristo (Holy Christ). Representatives of the Albarracín Community used to meet at the entrance to settle certain agreements. This chapel is one of the most important, along with the one at el Tremedal, where there were hermits.

El Santo Cristo

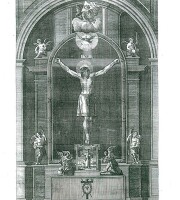

The crucified Cristo de la Vega (Holy Christ of la Vega) is one of the sculptures with the most artistic value in La Sierra de Albarracín.

Located in the chapel of the same name, it was made by Modesto Pastor Juliá, a sculptor from Albaida (Valencia) between 1872 and 1873 at his workshop in Valencia. It replaced another very ancient figure of the Christ, possibly from the 13th or 14th century, which was destroyed in a fire in 1872.

The sculpture, which is approximately 1.82 metres high, corresponds to the demands and wishes of the remedial commission, created by the Cathedral Council of 9 August 1872. In one of its communications, the aforementioned commission instructed the sculptor Pastor: “May the Crucifix inspire love, devotion, even more than respect, fear; may the perfect execution of his wounds, of the lacerations on his shoulders, back and knees, bruises and contusions, etc. produce compassion and feeling; may his incarnation, be like that of a corpse, and, in short, that it be considered a masterpiece.”

The cross of the Cristo de la Vega measures 2.95 by 1.84 by 0.26 by 0.09 metres. It rests on a simulated mountain of wood, made by Lorenzo Saez in 1912. At the foot of the cross lies the skull and crossbones.

The hypothesis that Pastor was inspired by the ‘Santo Cristo de Amor’ (Holy Christ of Love) by Juan de Mesa made in 1620 and currently located in the church of el Salvador in Seville is not ruled out: His head tilted at the same angle and crowned with thorns, closed eyes, blood stained forehead, three nails in his hands and feet, the way his feet were arranged, a sore in the same place on the side, etc. These are many coincidences that would support this theory.

Cristo del Amor by Mesa (1620) and Cristo de los Cálices by Montañés (1604)

However, the loincloth is completely different to the one by Mesa (Baroque style), whereas the one on La Vega is simple, and covers the top of the thigh on both legs. These, apparently, follow the classicism of Montañes, because they are proportionate and full of softness, which was a hallmark of the portrayals of Christ by the master of masters, Juan Martinez Montañés, a contemporary of Juan Mesa, whom he possibly influenced. If you look at the anatomy, the model of the cross and the loincloth in both figures, the similarities are unequivocal, and it is clear from the dates of creation who was the master and who the disciple.