Traditional Dress

Sierra de Albarracín

The traditional clothing of the Sierra de Albarracín that prevailed in the 18th century until the end of the 19th century, and that has marked the characteristics of the folkloric apparel, depended among other things, on the original materials that existed in each area and that were used to make them.

In spite of this, there are certain elements that can influence the characterization of typical costumes, although they are not determining factors, according to several scholars. In this case, the low winter temperatures of the Sierra de Albarracín, whose average altitude is close to 1,000 meters above sea level, and the landscapes of an abrupt mountain range, have established the use of certain garments in this highland.

The professor maintains that the harshness of the weather was resolved with a good shawl or scarf, but did not result in a definite design for the outfits. This circumstance, however, can be seen in the use of certain materials, such as the wooden soles of shoes, or in the thick fabrics used to make the clothes.

However, there are some very characteristic garments such as the elaborate 19th-century men’s shirts, which are a curious example of the transformation of a garment from the cattle merchant sector, magnified with rich fabrics and bright colours to become the attire of celebration and ceremony.

As with the weather, the geography of the Sierra de Albarracín, on the border of Cuenca, has resulted in a series of influences from other provinces that have remained intact throughout history; there have even been extensions of one land to another, allowing for other customs to be introduced, and of course, certain elements of Cordellate cloth clothing.

All this defines the typical Sierra de Albarracín costume with certain variations:

The women wore open cloth or goatskin shoes, stockings, patterned or otherwise, made of blue or white worsted cotton, a relatively short skirt, small apron, narrow-sleeved doublet, neck scarf, and shawl of heavy fabric or flannel, depending on the season and the occasion.

The men wore open espadrilles, and instead of socks they wore short white stockings. The rest of their clothing was completed with short knickerbockers made in local Cordellate cloth, black Cordellate vest, cape, blanket or scarf also made of Cordellate, with or without a hat, and if one was worn, it was made of felt with a low crown and a wide brim. The cummerbund (made of yarn and very exceptionally silk) was usually blue or purple and the jacket was sometimes replaced by a shirt. The cape, the hat and the jacket were ceremonial clothes and for work. At home or to go out into the country they usually went in shirt sleeves or ‘a forro’ (wearing the ‘undergarment’).

The women wore fitted skirts, pleated or collared, and a merino shawl crossed and fastened to the waist. The men wore tight-fitting knickerbockers with no marinetas or hanging tassels, tied under the knee, high-neck crossover vest and short, tight-fitting jacket in dark colours.

Purificación Atrián, former director of the Provincial Museum of Teruel, notes there are substantial differences in the women’s outfits between public holidays and working days, according to the permanent collection on show in the Museum’s display cases.

For the latter, the ‘cordellate’ cloth was used. It was made locally, and was also used to make the shepherdesses’ skirts, to protect them from the cold and rain. Atrián affirms that these skirts “could be plain, although enhanced or adorned with a strip of another colour, sometimes trimmed, which was then stitched onto the lower hem”. Locally made ‘cordellate cloth’ was used for a good number of male and female garments, not only for working attire, but also for festive costumes.

In the latter case, cordellate was used to make underskirts, over which a saya (skirt) and an apron were worn, made in blue with fine white vertical stripes. On the torso they wore a cotton chambra (blouse) that was occasionally embroidered as adornment on the cuffs. A large woollen shawl, crossed at the front, topped with a scarf, protected the woman from the cold, together with a smaller, more brightly coloured scarf that covered her head.

San Antonio Abad

January 17th

San Antón, the patron saint of animals, is celebrated by blessing the animals. It was customary to bless a piglet that was released in the streets; it was everyone’s duty to feed it and then take it back to its pen at night. The date of its slaughter and benefit vary according to the data compiled. In the evening, bonfires are lit in all the City’s neighbourhoods, with firewood collected on the river bank by the young people and from private donations. People gather around the fire, where potatoes, somarro, and pig snouts are cooked. It was customary for each person to warm themselves and cook their meat on the neighbourhood fire; to bypass the norm was punished with sticks until recently.

Nowadays, visitors can approach any of the bonfires in the various neighbourhoods, to grill their meat. The people of Albarracín are very friendly to visitors and usually offer them some of their food and a good sip from the wineskin.

The biggest and most popular bonfire among locals is the one in El Arrabal, with flames reaching up to ten metres high at its height, whereas visitors are drawn to the one in the Plaza Mayor square.

For reasons related to the work calendar, the bonfires are no longer held on the day of San Antón, moving this tradition to the Saturday closest to 17th January.

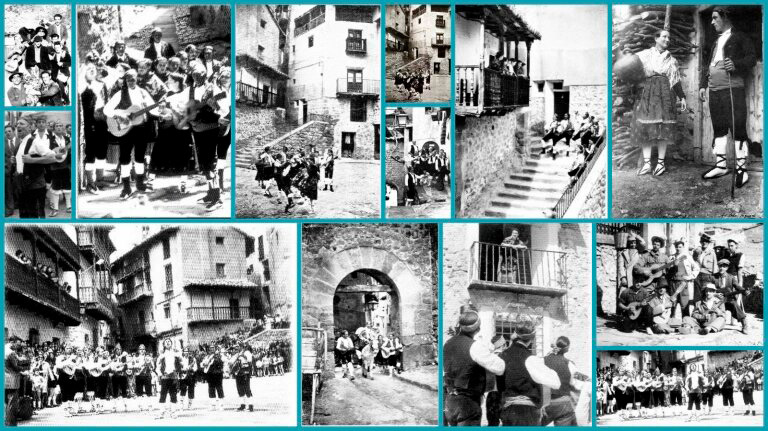

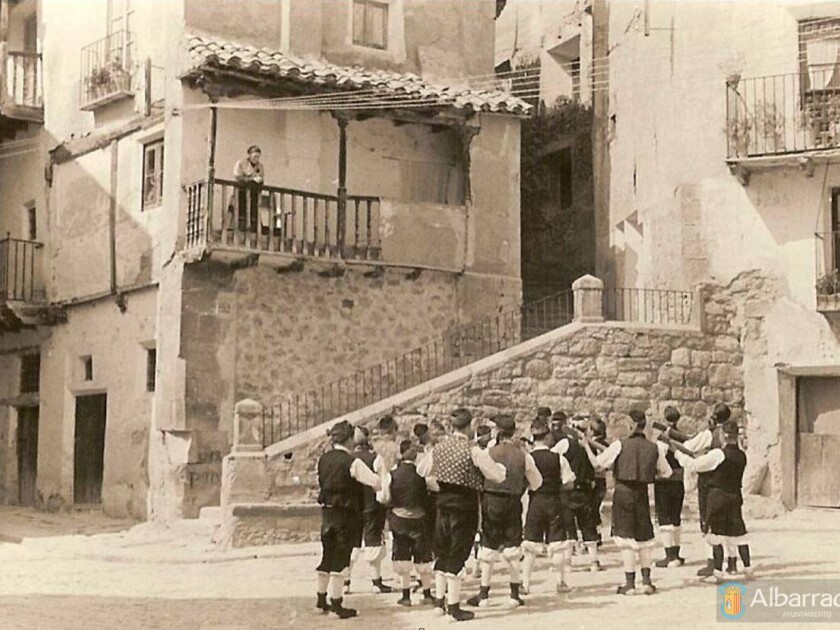

Los Mayos

April 30th

The festival of Los Mayos could still be seen almost in all its glory up until about twenty years ago. Today it has become a congregation of the most diverse cross-section of people, in order to have fun; to the point that we can talk about a performance for visitors.

It used to be a private celebration, of groups or teams, who sang couplets to the local mozas (eligible young women) describing their attributes. On 30 April, the mozos (eligible young men) met in a house or tavern, where they snacked on hearty dishes; afterwards, the Mayas were ‘auctioned’, consisting of bidding for the chosen maiden. The winner was the girl who received the highest bid. The Virgin Mary also entered the auction. The feasting began with the Mayos singing to Her in the doorway of a church. The Mayos couplets are sung by the young men while they dance a jota, accompanied by guitars and mandolins, then a variable number of stanzas (according to the singer and his group), and it ended with a farewell jota. There is no room for rudeness within the Mayos, as the stanzas are the same for the Virgin as they are for the young women (mozas), but they are sometimes sung to ‘punish’ the Maya who did not accept the wooing of her Mayo, or who did not give him the obligatory dozen eggs. Here are two of the prettiest stanzas:

Translated Version:

“There is no pen,

nor painter, nor poet,

nor brush that could capture

your gracious beauty”

(Choral response)

“nor brush that could capture

your gracious beauty”

“These are your eyes

like morning stars,

when you open them

the night fades away.”

Original Version:

“No hay pluma que sirva,

ni pintor, poeta,

ni pincel que copie,

tu gentil belleza”

(Con el estribillo a coro)

“ni pincel que copie

tu gentil belleza.”

“Esos son tus ojos

luceros del alba,

que cuando los abres

la noche se aclara.”

Los Mayos de Albarracín. Version sung by Celia Sáez in 1976.

1

The thirtieth hath come,

April’s end is here.

With May’s arrival,

Be happy, my dear.

May’s now upon us,

A welcome be said,

Let it water dells,

Let maidens be wed.

May came and bade me

Get thy permission,

And show thy beauty

In painted rendition.

No word you do speak,

We might be forgiven,

If we should assume,

That license is given.

Thy head held up high,

Though tiny and small,

Graced by a daisy

On top of it all.

1

Ya estamos a treinta

del abril cumplio

alégrate, dama,

que mayo ha venido.

Si mayo ha venido,

bienvenido, sea,

regando cañadas,

casando doncellas.

El mayo me ha dicho

que pida licencia

para dibujarte,

de pies a cabeza.

Como no contestas,

ni nos dices nada,

señal que tendremos

la licencia dada.

Esa es tu cabeza,

tan rechiquitita

que en ella se forma

y una margarita.

2

Thy hair like a skein

Of pure solid gold

That once it’s been combed

Is a sight to behold.

Upon thy forehead

The battle beckons,

And there King Cupid

Brings forth his weapons.

E’er so slightly arched

Thine eyebrows I see

Like rainbows in heav’n

When heav’n your face be.

Now cometh thy nose,

The tip a sharp sword,

That pierceth all hearts

With ne’ery a word.

And what of thine ears?

Like pendants they hang.

Bells to call people

With a brilliant clang.

2

Ese es tu pelo,

madejita de oro,

que cuando lo peinas

se te enreda todo.

Esa es tu frente,

frente de batalla,

donde el rey Cupido,

presentó sus armas.

Esas son tus cejas,

un poquito arquiadas,

son arcos del cielo

y el cielo es tu cara.

Esa es tu nariz,

puntita de espada,

que a los corazones

sin sentir los pasa.

Y esas tus orejas

que cuelgan pendientes,

parecen campanas

“pa” llamar la gente.

3

Lips like doorlatches

Are luscious and round,

And when they open

Make ne’ery a sound.

I seeth thy mouth

Red like fresh cherry,

Small delicate teeth

Red tongue so merry.

Here now is thy throat,

Delicate, demure.

When you drink water,

Everything is pure.

Here are thy shoulders,

A double staircase:

One up to heaven,

One back to the base.

These now are thine arms,

Like two rowing oars,

Guiding all sailors

Back from their tours.

3

Esos son tus labios,

son dos picaportes,

que cuando los abres,

no se oye ni un golpe.

Esa es tu boca,

tan recolorada,

de dientes menudos

y lengua encarnada.

Esa es tu garganta,

tan pura y tan bella,

que el agua que bebes

toda se clarea.

Esos son tus hombros,

son dos escaleras,

“pa” subir al cielo

y bajar por ellas.

Esos son tus brazos,

parecen dos remos,

que con ellos guías

a los marineros.

4

Thy wonderful hands,

As everyone knows,

Turn all that they touch

Into a red rose.

Thy waist is as slim

As reeds by a stream

Bending and swaying,

A flowering dream.

There is thy belly,

Like a drum so round

And when you touch it

There is such a sound!

Now we have come to

Thy more private parts

Of which I can’t speak

For I know them not.

Here cometh thy thighs

Of solid gold made

Where for the building

The foundation’s laid.

4

Esas son tus manos,

tan maravillosas,

que todo que tocas

se convierte en rosas.

Tu cintura un junco,

es un junco al río,

todos van a verlo,

cuando está florido.

Esa es tu tripa

que parece un bombo

que cuando la tocas

se retumba todo.

Ya vamos llegando

y a partes secretas

donde yo no puedo

dar razones ciertas.

Esos son tus muslos

de oro macizo,

donde se sostiene

todo el edificio.

5

There are thy two legs

So lovely and prim

The top of them thick

The bottoms are trim.

Then cometh thy feet,

Small steps they do take.

And with each you show

Your charm, no mistake.

Small shiny white shoes

And long bright red tights,

Wee is the young girl,

But truly a delight.

This song has described

Each of your features,

And May Day highlights

This lovely creature.

5

Esas son tus piernas,

tan bien accionadas,

por arriba gordas,

por abajo delgadas.

Esos son tus pies,

de paso menudo,

con ese pasito,

encantas al mundo.

Zapatito blanco

y media encarnada

pequeña es la niña,

pero muy salada.

Ya te hemos cantado

todas tus facciones

sólo falta el Mayo

que te las adorna.

Corpus Christi

60 days after Easter Sunday / May or June

The solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ is intended to proclaim the real presence of Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, worshipping him publicly. Specifically, Corpus Christi is on the Thursday following the ninth Sunday after the first full moon that appears in the northern hemisphere in spring. In the case of Albarracín, it has been moved to the following Sunday to adapt to the work calendar.

Formerly, and until about 50 years ago, the brotherhoods and guilds of the city still participated along with the entire Cathedral Council, the parish priests and members of all the parishes, creating quite a spectacle with all the banners and flags on display.

At present, and following a centuries-old tradition, during the course of the Corpus procession, a portable altar is installed in the place where the Puerta de Hierro (iron gate) was located (without most of the Albarracín locals knowing the reason). Recent archaeological research has helped us understand why this altar is placed at this spot, which has no other meaning than to make it coincide with the entrance to the City through the Puerta de Hierro.

This gate was to serve as the main and sole entrance to the city as rebuilt and enlarged by Hudail Ibn Razín (16th century). We thought that it had a superior importance in some way to the other gates, because in the 17th century the new Prelate, who came to take possession of the diocese, was welcomed at this gate.

At the intersection of Calle del Chorro and Calle Azagra we can see a wooden cross over the lantern, in remembrance of a priest who was murdered during the Corpus Christi procession. As a consequence of the crime, the town erased half of the coat of arms on the house that now belongs to the Cooperativa Católica del Campo cooperative.

At present, only the brotherhood of the Santísimo Cristo de la Vega participates, accompanied by the children who have received their First Communion during the year and the municipal corporation bearing maces, which honour the Consecrated Host, in a unique procession. The historical Bourbon costume of the city’s sergeants-at-arms is worthy of mention, with their half-chasubles bearing the City’s coat of arms and their caps decorated with ostrich feathers.

La Virgen del Carmen

July 4th to 16th

The procession of the Virgen del Carmen begins in the church of Santiago, goes down to the Plaza Mayor, from where it leaves towards the Portal de Molina; before that we will stop in the Placeta de la Comunidad, which is adorned for the occasion to collect the image of the Virgin in the centre with a brief prayer there. The procession continues up the street, passes the Portal de Molina and rests before the fountain, at the junction of the streets, where the locals of the barrio del Portal neighbourhood prepare an altar to place the image, while the priest and companions pray. Continuing along Calle de la Virgen del Carmen, where there is ivy arch, built specifically for this day, with the wording Viva la Virgen del Carmenn (long live the Virgin of Carmen). Without stopping until reaching the chapel, the procession continues its ascent, which will soon leave the cobbled street to continue along a dirt road that was once called the Camino de Molina de Aragón, then Torres, then Sierra and now the Virgen del Carmen. As the procession ascends, the bells of the Church of Santiago and the chapel ring or peal and the pilgrims sing and pray intermittently.

A little further up there is a peirón (ancient monument) almost in ruins, where walkers deposit stone slabs (pagan Roman custom), in a sign of offering while praying an Our Father or a Hail Mary; this act is not usually done on the day of the Virgen del Carmen, but on any other day, while taking a walk around the area or coming here to pray in the atrium of the chapel.

We are now at the end of the route; behind us is the city with the sound of the bells of Santiago, and we can start to hear the arrival of the procession being announced from the chapel. The image of the Virgin is brought inside, along with all the priests and pilgrims who can fit, as the chapel is very small; and after some prayers, the ceremony is considered finished. The Virgin will be kept here throughout the year until a few days before the next procession, when the santera or fraternity and its escorts bring the image once again to the Church of Santiago so that the act can be repeated another year.

Patron Saint Festivities

September 8th and 14th

Albarracín celebrates the day of its female Patron Saint, Santa María (Saint Mary) on 8 September and its male Patron Saint the El Cristo de la Vega on 14 September, with the two festivities almost uniting.

The Albarracín festivities have a reputation for being the best in the entire region and are attended by almost everyone from the surrounding area. They consist of night-time street parties with well-known and lesser-known musical ensembles, concerts, processions, brass bands, novilladas (bullfights with young bulls), cabezudos (large-headed cardboard carnival effigies) accompanied by dulzainas (a wind instrument)… Albarracín changes colour. The Plaza Mayor is enclosed with pine trunks and the ground is covered with sand for the bullfights; with this, the town looks even more like a medieval city. These days are perfect for those who like night life and, especially, people who love running with bulls, because Albarracín possesses one of the most dangerous ‘runs’ in Spain; when the bulls are released they run through the city’s narrow, sloping streets right down into the main square.

The 7th September (the day before the Patron Saint’s day) is usually a day of merrymaking in the main square; on the 8th (the Patron Saint’s day) the festivities take on a slightly more serious tone.

Formerly there was an auction for enclosing the square enclosed with pine trunks, spreading of the sand for bullfighting (which normally fell to the local lads), the departure of the cabezudos (the big-headed carnival figures, for which adolescents and lads bid) and the seating or boxes located between the arches of the Town Hall.

Right now, due to the complexity of enclosing the square for bullfights and assembling stands, it isn’t possible to hold the auction, but it is worth attending the bidding and auction on another occasion due to its uniqueness.

On the 13th (eve of the Patron Saint’s day), a public street party usually takes place, as on 14th (Patron Saint’s day); at the end of this day, around 5 or 6 in the morning, the sand is scattered around the square, turning it into a somewhat peculiar bullring. A few hundred firecrackers are thrown to help the lads spread the sand.

Normally, around midnight, the bullfighting clubs dressed in white, with red or green scarves and sashes enter the Plaza Mayor square, accompanied by a brass band, to listen to the toast and to officially start the festivities. People visiting Albarracín seeking peace and quiet should avoid visiting us from 13 to 17 September.

The 15, 16 and 17 are days full of frenzy, with bulls and calves, brass bands, street parties and large crowds of people on the street celebrating their feast days, mainly centred around the Plaza Mayor square.

Holy Week (Semana Santa)

Holy Week in Albarracín is part of the Holy Week festivities of Aragón, characterised by their solemnity, austerity and the respectful silence of their processions, only interrupted by the sound of drums and bass drums. The beginning of Holy Week is initially marked by Lent, which begins 40 days before Easter Sunday and ends on Palm Sunday. It is on this day that Holy Week officially begins, ending on Easter Sunday.

Among the different events that take place over these days, apart from the purely religious acts, two days are celebrated with some of the other municipalities that form part of the drum and bass drum route of the regions of the Sierra de Albarracín and the area of el Jiloca, making these few days very crowded and busy.

On Holy Thursday, a procession is made from the Church of Santa Maria through the streets of the historic old quarter with drums and bass drums, culminating with a performance in the Plaza Mayor.

On Good Friday, the drum and bass drum bands stop for a break at 12:00 noon; this is usually accompanied by some numbers on the drum and the bass drums played alongside members of the other associations from the province of Teruel. In the afternoon, the procession of the Stations of the Cross leaves from the Church of Santa Maria.

On Holy Saturday, in the evening, in the Cathedral of El Salvador, the Gloria is performed by the Drums and Bass Drums Association of Albarracín.

Easter Sunday, there is a celebration of the Lord’s resurrection in the Church of Santiago.

Red Plaster (El Yeso Rojo)

The only traditional production of red plaster is in Albarracín. It is manufactured in an artisan way with local stones, resulting in a salmon-pink product. Coatings made with this material have a satisfactory performance both during construction and in terms of durability, making it the material of choice for restoration work on plaster facings.

Gypsum is formed from the evaporation of small shallow lakes in tidal plains; this geological phenomena results in a landscape of calcareous banks on which the city is built, and softer terrain in the outskirts: sands, clays, marls and gypsums. All in relatively disordered masses of grey and red colours.

Recovery of traditional plaster

The rehabilitation of the historical complex of Albarracín has been carried out by building a traditional plaster furnace to obtain the necessary material for the work. It used to be manufactured manually, but with industrialisation the artisan trade was disappearing, so the family of Antonio Meda started to manufacture plaster artisanally until the 1960s, when industrial plaster, originating from Teruel, began to be used among the masons of Albarracín.

In the 1990s, several workshop schools appeared and were successful in restoring the dying trade with a material that was very similar to the original, completely compatible and without any problems in its use or due to cracking. The Regional Government of Aragón has decided to support the application of this traditional material to the façades of buildings under rehabilitation, subsidising 100% of the cost of the material, believing in the importance of maintaining the predominant salmon-pink tone on most buildings.

The geological particularities of the gypsum deposits in this region produce two varieties of gypsum stone, one grey and the other red, both of which are used at the same time to manufacture plaster products. There are, therefore, two different products: a red plaster, of a salmon-pink colour, made by mixing grey and red stones, and a plaster called blanco or azulete (white or blue), with soft ochre tones.

Since 1999, the costs of both types of plaster have been subsidised for restoration works in Albarracín. In addition to the walls, the blue plaster is sometimes used in vaults and staircases.

Materials and manufacturing process

Two types of gypsum stone that emerge in the quarries near Albarracín are used to manufacture red plaster, dark grey stones bathed in clays.

Both gypsums also have silica impurities, both amorphous (only recognisable by microanalysis) and crystallised, in the form of Jacinto de Compostela quartz. Using semi-elliptical stones of about 30 cm in diameter, an arch is formed on sandstone supports and the gypsum is dehydrated by applying a sustained fire for 18 hours. The red stones have a smaller presence in the furnace than the grey ones, and are positioned in places where the fire takes longer to reach. Iron oxide acts as an agent that lowers the transformation point of phases. Intuitively, in traditional manufacturing it was known that less energy is required to completely dehydrate red stones than grey stones. After firing, it is then ground, mixing all the materials, which are then sifted. The resulting product is bagged, reaching a uniform particle size that varies from very fine (less than 63 µm) to particles of 4 mm. Its water properties are also interesting, with an environmental absorption coefficient of 20%, placing it among the plaster products with the best reaction to water. In general it can be said that the artisanal plaster currently manufactured in Albarracín is a suitable product for the tasks of restoring old traditional exterior plaster walls, Albarracín being a current example of its practical application.

In this way it is possible to maintain all the properties and qualities that make this material a product of enormous architectural richness in terms of hardness, elasticity, impermeability and ecology; in addition to a mechanical performance to the changes of temperature for later sale and distribution as a product manufactured in an artisan way.

Some living testimonies that endorse the virtues of ‘Albarracín Plaster’ can be seen in its application during the restoration of recent buildings of historical and patrimonial importance, and using the same composition and artisanal manufacturing process as the original, are:

– La Aljafería Palace in Zaragoza, current seat of the courts of Aragón.

– The hanging houses of Cuenca.

– The Alhambra in Granada.

– The Papa Luna Palace in Illueca.

– The Episcopal Palace in Albarracín, Europa Nostra.

More information

Complementary information for your visit to Albarracín