Protected Landscape of

Los Pinares del Rodeno

Located in the Sierra de Albarracín region and a few minutes from the Historic Centre of the city of Albarracín, is this unique space, characterised by the multitude of geological forms it is home to, in addition to its relationship between geology, flora, fauna and the traditional activities of man.

However, what really makes this landscape unique is the discovery of significant rock art murals. For this reason, in 1995, the General Council of Aragon created the Protected Landscape of los Pinares de Rodeno, a title awarded thanks to its natural value, and also the presence of several spaces with Levantine rock art paintings.

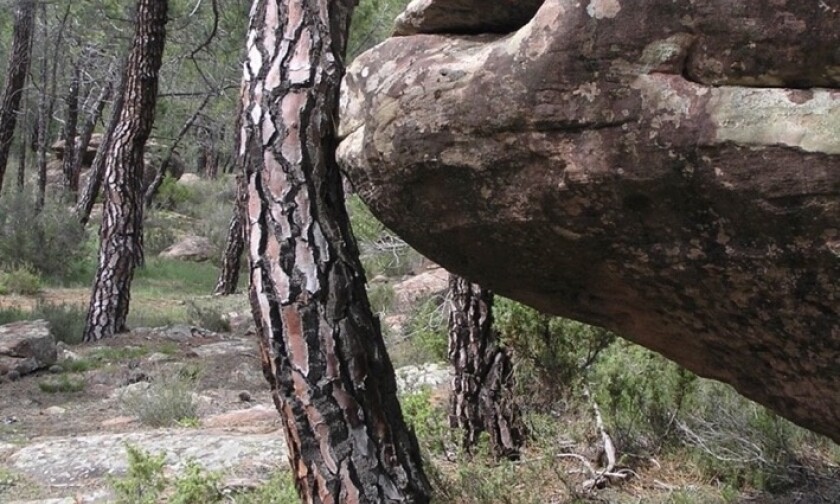

Regarding its geology, red sandstone predominates. Thanks to atmospheric agents such as rain, wind and temperature changes, which have exerted pressure over time, this material has acquired a multitude of peculiar shapes. In addition, the watercourses sandwiched between these rocks have caused the appearance of scarps, gorges and alleys.

On a smaller scale, these atmospheric agents have also sculpted whimsical shapes such as tafoni (hemispherical holes in the rock wall), alveoli (larger holes in the rock), gnammas (circular depressions in the rock surface) and Liessegan rings.

Regarding the flora, the most characteristic species in this environment is the rodeno pine. It is an arboreal species with great facility to grow on land with a lot of rock; it is also known by the name of resin pine. In addition, the area includes other species such as common juniper, rockrose, heather and lavandula, as well as aromatic species such as thyme and rosemary.

In ravines and more humid areas there are poplars, willows, hazelnut and holly, while in limestone areas the abundant red pine gives way to black and wild pines.

The Protected Landscape is also the habitat of a multitude of wildlife species. The mammals include wild boar, roe deer, deer, fox, European wildcat and hare. Among the birds, the pine forests are a refuge for tawny owl, hawk, booted eagle and goshawk.

Reptiles are represented by long-tailed lizard, ocellated lizard, Montpellier and ladder snakes, and the amphibians include natterjack toads, spur toads and spotted toads.

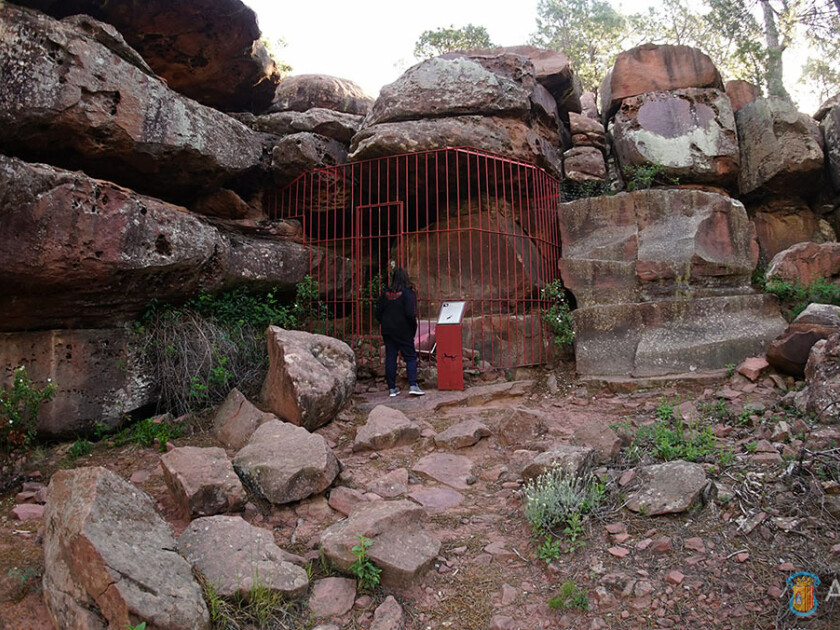

Despite being an area that is quite inaccessible to man, humankind’s presence dates back to prehistoric times, as evidenced by the numerous manifestations of Levantine rock art, scattered in shelters and cavities, as well as the remains of Celtiberian and medieval settlements. The uniqueness and richness of the rock art representations led to it being declared an Asset of Cultural Interest in 1985 and Albarracín Cultural Park in 1997.

The rock paintings in these shelters are considered Levantine art, since they have characteristics typical of this art such as: the schematic figure, the everyday scenes of hunters and gatherers, as well as the great presence of red.

Source: Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa

Albarracín Cultural Park

Rock Paintings (Pinturas Rupestres)

The discovery of cave paintings in the shelters of Toros del Navazo and Cocinilla del Obispo in the surroundings of Albarracín by E. Marconell in 1892 was not only the first appearance of a panel painted with Levantine art in the Iberian Peninsula; above all, it was the beginning of a long process of knowledge, documentation, protection and dissemination of this artistic manifestation that, at the dawn of the third millennium, has turned the Sierra de Albarracín into one of the most unique and important rock art centres of our Autonomous Community, becoming a classic and obligatory reference in all works of a scientific or popular nature that have been published in the last hundred years, both inside and outside of Aragon.

Since the first scientific work on these first shelters with Levantine art, published by Juan Cabré and Abate Breuil in 1910, discoveries and subsequent studies have followed one after another. After the works by Cabré in 1915 and by Obermaier in 1916, in which the Albarracín shelters appear, and within a climate of strong scientific dispute between Spanish and French scholars regarding the origin and chronology of Levantine art, the Tormón cave nucleus was discovered, published by Breuil and Obermaier in 1927. In 1949 Martín Almagro unveiled the Doña Clotilde shelter and, before that, in 1947, Teógenes Ortego discovered the Bezas complex. But it was in the 1960s and 1970s when Martín Almagro discovered and studied the shelters of Camino del Arrastradero and Barranco del Pajarejo, sites that became part of the first group of rock art in the Sierra de Albarracín, published by Fernando Piñón in 1982.

Starting in 1985, a new generation of archaeologists, such as O. Collado, F. Gómez, M. A. Herrero, E. Nieto, J. Picazo and J. I. Royo, joined the investigation in the area, multiplying the discoveries of new shelters with rock paintings in Tormón (La Paridera and Las Cabras Blancas shelters), in Albarracín (Toro Negro and Lázaro shelters) and in Frías de Albarracín (Peña de la Moratilla Cave). But the most surprising and abundant finds have occurred since 1980, with more than 30 new sites with rock carvings in the open air scattered throughout the Sierra de Albarracín in places such as La Masada de Ligros (Albarracín), Tramacastilla, Pozondón and Rodenas.

All this effort has been recognised internationally with the declaration in December 1998 of the rock art of the Sierra de Albarracín as a World Heritage Site, along with the rest of the Mediterranean Basin of the Iberian Peninsula. Between the years 2000 and 2001, the Government of Aragon, through its Department of Culture and Tourism and the Cultural Park.

Styles and techniques in rock art

With the existence of artistic manifestations linked to Palaeolithic Art discarded for the moment, in the Sierra de Albarracín the two most representative prehistoric pictorial styles of the entire Mediterranean Basin are represented: Levantine Art and Schematic Art.

Along with these manifestations, sometimes occupying the same territory, but on most occasions with individual nuclei, we find a large number of sets of outdoor engravings, some dating to the prehistoric and protohistoric periods , but most from history, and which on occasion have lasted until the dawn of the 20th century.

Levantine Art

Levantine Art is an essentially pictorial manifestation developed outdoors, in covachos or shelters located in the main mountain ranges of the Mediterranean Basin of the Iberian Peninsula, from the Sudbéticas foothills to the Huesca Pre-Pyrenees. In Aragon, it is located throughout the main mountain ranges, although the finds are concentrated in the Vero River, near the Sierra de Guara, in Huesca; in Bajo Aragón, Zaragoza and Teruel; in the middle course of the Martín river; in upper Guadalope; in Maestrazgo and in the Sierra de Albarracín. In these nuclei, 63 stations with Levantine art have been documented to date.

It is art that is typical of human groups whose economic activity was based on hunting and gathering, and whose material culture is defined as Epipaleolithic, although it is also found in other groups of the Epipaleolithic tradition in the process of Neolithicisation. They are communities associated with a predatory economy and are concentrated in the wildest areas of our geography, in an ecosystem in which they can hunt species such as ibex, deer, wild boar, horses and bulls, as well as gather fruits, wild berries and honey. Levantine rock art is painted in a variety of somewhat sparing mineral colours, with a predominance of red and its different shades, along with black, white and yellow. The paintings are made using flat, contoured or striped inks, applied using bird feathers, an instrument that characterises the execution technique and the line of this type of art.

The Levantine art of the Sierra de Albarracín, in addition to its geological medium, has some elements that differentiate it from other groups. One of them is the predominance of deer, bulls and horses in the representations. The other is the large size of these animals, especially in the case of bulls. The last element is this group’s almost exclusive use of white paint, to the point that in some shelters it is almost the only colour (Toros del Navazo, Cabras Blancas).

Schematic Art

The arrival and expansion of Neolithic culture to Aragonese lands around the 5th millennium BC and the colonisation and exploitation of new spaces, meant the arrival in this area of people using a productive economy, where agriculture dominated with incipient livestock farming. These people brought with them new beliefs, which are reflected artistically in Schematic Art, which not only outlives the Neolithic period, but also persists in certain areas until the Late Bronze Age and the arrival of the Urnfield culture. Compared to the naturalism of Levantine art, schematic art is a new style that developed – like the first – in shelters, but also outdoors and both in painting and engraving, although always using symbols and abstractions in its iconography and reducing animals and human beings to their minimum conceptual expression. At this time, circles, cruciforms, spirals, serpentine shapes, branch shapes, reticulate forms, dots and bars are represented, together with zoomorphic and anthropomorphic motifs that express a hidden language behind visual codes that offer a graphic representation of a much more complex and elaborate spiritual and social world than in prior eras.

It so happens that the only shelter painted on a limestone medium in the Sierra de Albarracín is in the schematic style, in the Cueva de la Peña de la Moratilla de Frías in Albarracín, where the only painted equestrian scene is also found. The number of schematic painted stations is relatively small, but they are present in all the complexes; the Medio Caballo-Figuras Amarillas and Doña Clotilde shelters in Albarracín offer particularly spectacular representations, as does the aforementioned Cueva de la Peña de la Moratilla.

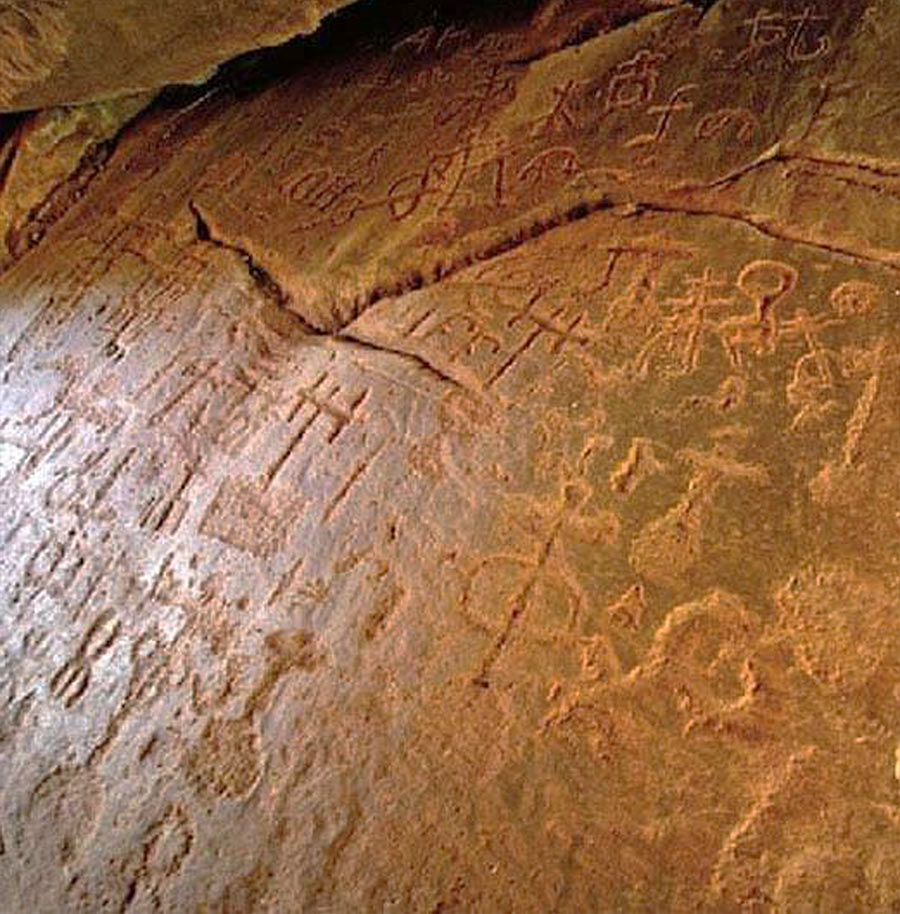

Postpaleolithic rock carvings in the open air

Until recently, only a few isolated examples of rock carvings in the open air were known in the Sierra de Albarracín. The engraved figures of cervids and equines in the Fuente del Cabrerizo shelter, of an uncertain date and difficult to assign to the Levantine style, can be assigned to the pre- or protohistoric period, although currently-existing parallels do not allow us to date them with any certainty to a specific artistic or chronological context.

The rock engravings are made in shelters, caves or rocky slabs in the open air, almost always on horizontal or slightly inclined surfaces, and only in a few cases on the vertical walls of the shelters. The only medium used is sandstone and the most common technique is percussion or perforation, either by means of a lithic or metallic instrument, generating motifs with more or less open U-shaped grooves. The rock engravings of the Sierra de Albarracín can be included in two large groups:

a) Engravings in a schematic-abstract style which date to prehistory or protohistory.

b) Engravings in a schematic style that were created between the 10th and 20th centuries. Among the prehistoric or protohistoric engravings, the motifs of bowls stand out, isolated or grouped, others joined with little channels, and of serpentine, circular, corniform, concentric, reticulated, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms. There are a few sites with these motifs, including Barranco Cardoso I in Pozondón, the circles engraved on the floor of the Medio Caballo shelter in Albarracín and Masada de Ligros, also in Albarracín, an authentic prehistoric sanctuary that may date back to the Final Neolithic or Eneolithic period.

Chronology and archaeological context of rock art in the Sierra de Albarracín

Much has been discussed among specialists throughout the 20th century about the origin, evolution and chronology of rock art, especially Levantine. After discarding the Paleolithic dating of Levantine art, initially proposed by Henri Breuil at the beginning of the 20th century, various proposals have been put forward throughout the second half of the century and are still the subject of bitter controversy in scientific circles today. The methodological application of the relationships between rock art and material culture and the systematic study of the archaeological context that is usually found next to certain painted or engraved panels, together with the analysis of the overlapping of different styles on the same panel (Levantine-Schematic or vice versa), has led to the development of two hypotheses:

a) Levantine Art is of Neolithic origin and contemporary to the schematic art on which it is superimposed.

b) Levantine Art appears in the Epipaleolithic period, coexisting with schematic art from the arrival of the Neolithic period, both in time and in the same territory.

With regard to schematic art, its archaeological contextualisation, associated with its parallels with the ceramic decoration of the Early Neolithic Cardial culture, found in various sites in the Valencian Community, or related to the wall decoration of a large number of boulders from the Early Neolithic from the Chaves cave in Huesca, allow scholars to ascribe the origin of schematic art to the Early Neolithic period, dating to around 5,000 BC. This seems to be confirmed in our case in the Doña Clotilde shelter, whose schematic panel could be associated with an archaeological level located in the same shelter that dates to that time period. The survival of schematic art throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Age seems to be confirmed with examples such as the Cueva de la Peña de la Moratilla in Frías de Albarracín, which is related to the Early/Middle Bronze Age El Castillo settlement. In some contexts, this persistence could have reached well into the Late Bronze Age and the arrival of the Urnfield culture.

With regard to rock carvings, we have well-defined archaeological contexts associated with some of the main sites in the region. Thus, the schematic engravings of La Masada de Ligros have several Bronze Age sites in their immediate surroundings; some panels are even covered with sediments in which materials from that time have appeared. Similarly, the protohistoric sites of Puntal del Tío Garrillas II in Pozondón and Moricantada II are each located next to Celtiberian settlements.

Significance and symbology of the Rock Art of the Sierra de Albarracín

More complicated than dating paintings or parietal engravings is understanding the complex world of beliefs, rituals and motivations that led the primitive settlers of the Sierra de Albarracín to engrave or paint motifs on the sandstone rock panels that, in many cases, we are not able to interpret. Over the last hundred years, researchers have been contributing theories – some more intriguing than others – regarding the interpretation of these artistic manifestations, with none to date having managed to supersede previous or simply different ones.

From thinking of the decorated shelters as sacred spaces, where certain rituals were performed, to considering the panels as narrative representations of daily events, or the theories that consider Levantine art as a territorial mark or delimitation of the hunter-gatherer people in response to the rapid advance of Neolithic peoples and their schematic art, all these theories seem to have some truth to them, even the most recent ones that associate schematic anthropomorphic representations with a graphic representation of the political/social structure of the Neolithic or Chalcolithic human groups.

With regard to the artistic manifestations of the Sierra de Albarracín, we want to highlight some key points. The sanctuary status of some complexes, such as La Masada de Ligros, is undeniable, given the location and agglomeration of shelters with engravings, as well as the attempt to sacralise certain natural spaces. Other sites seem to have been associated with controlling passage or territories, and still others have an explanation in the context of the pastoral culture of the Sierra de Albarracín and the phenomenon of transhumance, as occurs in some sites with engravings in Ródenas or Tramacastilla, such as Peña del Jinete or Barranco del Conejar.

Source: Cartillas Turolenses

Maps

Location of the Cave Paintings of the Cultural Park

Routes

Hiking in the area of cave paintings

- Sendero PR-TE117 Albarracín – Área Recreativa del Navazo

- Sendero SL-TE 20 Pinturas Rupestres

- Sendero PR-TE 115 Recreativo del Navazo – La Losilla

- Sendero SE-TE 21 CI Dornaque – Pieza Llana

- Sendero SL-TE 22 CI Dornaque – Barranco de las Tajadas – Peña del Hierro

- Sendero SL-TE 23 Casa Forestal de Ligros – Campamento de los Maquis

- Sendero SE-TE 24 Las Olivanas

- Sendero SL-TE 25 Las Tabernillas – Laguna de Bezas

- Sendero PR-TE 116 C.I. Dornaque – Laguna de Bezas – C.I. Dornaque

- Sendero accesible: C.I. Dornaque – AR Fuente Buena

- Sendero accesible SL-TE 27: Pinturas Rupestres – Mirador de Peñas Royas

Additional information

Since 1892 when E. Marconell discovered the first two shelters with Levantine Rock Art in the Iberian Peninsula, Prado de los Toricos del Navazo and Cocinilla del Obispo, numerous projects have studies these manifestations and their cultural world. The researchers who have dealt solely with this subject or included it in summary works include: H. Breuil, H. Obermaier, J. Cabré, E. Hernández Pacheco, Camón Aznar, M. Almagro Basch, E. Ripoll, A. Beltrán, F. Piñón, J. Picazo. and O. Collado. In addition, other researchers have dealt with aspects such as the landscape, natural environment, forms of erosion, forest exploitation, farmhouses, ways of life, property structures, etc.

Rock Art and the other elements that make up and have shaped the environment form a barely altered natural and anthropic landscape that deserved the recognition of the 1986 Meeting in Albarracín, directed by A. Beltrán, from which the proposal came about for the creation of the Cultural Park and its Cultural Centre for Rock Art Studies.

In recent years, the prospecting, review, documentation and excavation work, carried out by O. Collado, M. Herrero and E. Nieto, have provided extraordinary results, locating new panels and numerous lithic finds through the progressive application of technical advances designed for other sciences, such as the use of electric light of different spectra and photon size, with which excellent results are achieved for viewing white figures, which are otherwise imperceptible to the human eye.

Compared to what we can see in other regions with Levantine cave manifestations, that of Albarracín forms such an evident unit and is an exception in terms of its landscape, themes and techniques, style, pigmentation and sizes, thereby making these artistic manifestations an obligatory point of reference for the study of the Universal History of Art and Man.

Although Spanish legislation, in cultural matters, does not define what a Cultural Park or Archaeological Park is, scientific circles are petitioning different administrations for such an entity to be created and legally defined, as one of the best solutions for the protection, conservation and dissemination of Sites of Cultural Interest (B.I.C., former National Monuments), both individually and grouped together, but always integrated into the landscape, which from the human point of view has been altered, modified and adapted to the anthropic needs of different historical eras.

While in Spain we must start by developing the Spanish Historical Heritage Law of 1985, or the autonomous sectoral Decrees or Laws so that they can define Cultural Parks, in several countries such as Germany, Italy, Mexico, Australia, the United States, Lesotho and Tanzania these parks have been operating for many years, sometimes with the international cooperation of UNESCO. In our country, prior to 1986, only the Valltorta de Castellón project was known, whose execution is currently stalled. It was in 1987 when the Albarracín meeting gave rise to the proposal for the creation in Aragon of the Vero River (Huesca) and Albarracín (Teruel) Cultural Parks. Other similar initiatives related to rock art have since arisen in Calasparra-Cieza (Murcia) or with archaeological objectives such as Segóbriga (Cuenca), Tarraco (Tarragona), Ampurias, etc. These last initiatives were promoted by the Ministry of Culture, which calls them Archaeological Parks (Madrid 1989).

Due to these 1987 initiatives, in Aragon, Law 12/1997 of 3 December of Cultural Parks of Aragon was finally passed, and specifically Decree 107/2001 of 22 May, which created the Cultural Park of Albarracín.

As we have seen, Cultural Parks do not necessarily need to have rock art as their primary purpose, but it can be any historical or artistic manifestation: archaeological sites, groups of typical buildings, castles, etc. In the case at hand, the Cultural Park with Rock Art aims, firstly, to protect this art from anthropogenic and natural aggressions, preserve it, document it and disseminate it by organising visits and in the context of its landscape, nature and traditional life. That is, Cultural Parks are created to allow for the use and enjoyment of a group of Sites of Cultural Interest (shelters with rock art), within a landscape and natural environment, ensuring this use is compatible with the protection and conservation of historical and cultural manifestations, which must be studied and documented as a guarantee of their conservation, while allowing traditional life to continue: grazing, resining, hunting, agriculture, etc., the manifestations of which should also be protected, conserved and disseminated (farmhouses, farming and resining tools, huts, etc.).

We cannot go on to explain what a Cultural Park with Rock Art, like the one in Albarracín, is without offering a brief introduction to explain the type of people who painted it and the characteristics of this art that some prehistorians call Levantine rock art.

According to Antonio Beltrán Martínez, Levantine or post-palaeolithic rock art originated around 6,000 BC, coinciding chronologically with epipalaeolithic culture. The oldest manifestations of its naturalistic style (Phase II) are found here; the best examples are the white bulls (a colour exclusive to Albarracín), which we find in Cocinilla del Obispo and Prado del Navazo. Beltrán’s phase III corresponds to the moment in which goats are represented in the Medio Caballo shelter, deer such as those at Olivanas, Tajadas de Bezas and Figuras Diversas, accompanied by stylised and static-looking human figures such as those at Navazo, Medio Caballo and Olivanas. Phase IV, which Mr. Beltrán Martínez calls Stylised Dynamics belongs to the Neolithic era; the deer-bulls at Olivanas, the archer at Callejones Cerrados, the equines of the two Caballos belong to this phase. Phase V (Aeneolithic 2,000-1,500 BC), the so-called Static, Semi-naturalist, Semi-schematic phase, would include the shelter of Lázaro, Tío Campano, the first phase of Doña Clotilde and El Pajarejo; finally, phase VI, or the schematic phase, encompasses the second phase of Doña Clotilde, characterised by the serpentine, anchoriform signs.

We can echo the words of H.G. Bandi, who when referring to this Spanish Levantine art said: “it was the most vivid legacy that prehistoric man has transmitted to modern societies”. This is because this art allows us to contrast the hunting and gathering economy, which was already manifested by its lithic tools. It also tells us about social aspects such as the Pajarejo dance, the Lázaro shelter confrontation, hunting and pursuit of animals, domestication or contacts of another nature between men and animals. Others have seen religious or spiritual aspects in this art, such as totems. Looking at these paintings, we find ourselves before an open book, the first open book in prehistory in which man openly participates through his own representation. Hence the importance protecting and conserving it and the need for the scientific community to study and disseminate it.

It differs from the so-called Franco-Cantabrian art, as a general rule, in its chronology (35,000 BC/compared to 6,000-2,500 BC for Levantine art), culture (Paleolithic/post-Paleolithic), location on the peninsula (N/S and E), location (cave/shelter and rarely cave), polychromy (Yes/No), human representations (exceptions/abundant), use of the engraving technique (abundant/few examples). These are differences pointed out only as a very general introduction, since in each point presented there are numerous nuances, but it will help the visitor who discovers this art for the first time to identify it.

Origin

The park was born from the recommendations made by several researchers, led by Mr. Antonio Beltrán Martínez, to the Aragonese regional government, within the conclusions of the “Colloquium on the Protection, Conservation and Diffusion of Aragonese Rock Art”, held in Albarracín in April 1987.

Subsequent meetings in Caspe in 1988, Zaragoza in 1989 and Zaragoza in 1990, confirmed the political will of the D.G.A. to create the park, which in 1990 led to the hiring of archaeologist Octavio Collado Villalba to draft the research and investment project. These events resulted in the drafting of Law 12/1997 of 3 December of Cultural Parks of Aragon, and specifically Decree 107/2001 of 22 May, which created the Cultural Park of Albarracín.

Location

It occupies almost the entire sandstone outcrop of the south-eastern Sierra de Albarracín, and its central axis is the road that joins Albarracín, Bezas and Tormón. The Cultural Park not only affects these three municipalities, as the municipalities of Rodenas and Pozondón were included at the last minute. In this park there are six complexes with rock art: El Rodeno de Albarracín, Tajadas de Bezas, Olivanas, Ligros and Pajarejo de Albarracín, El Prado de Tormón, the engravings of Pozondón and those of Rodenas.

Access

Due to the proximity of this rock art complex to the City of Albarracín, it can be accessed on foot or by vehicle, with a maximum distance of approximately 5 km.

On foot, we follow the path parallel to the Reguero stream, to the Cabrerizo spring, where it the stream originates. This path starts where the general signpost for the Park is located. Once at the spring, a path leads us to the road, and one kilometre further up we will find the information centre and the general sign panel.

By vehicle, follow the signs to the car park; 100 metres away is the information centre. The use of vehicles is prohibited for routes within the complex.

Scenery

If we have chosen to walk, which takes just over an hour and a half, we will be able to see and enjoy a wet, cool landscape that is green all year round, as well as springs and the curious shapes of the sandstone, which cannot be seen by car, which only allows us to observe the sandstone rims (“visors”), the pines that grow in the cracks of the cliffs and a grey, dry landscape to our right.

The landscape that makes up this Cultural Park Complex has a singular beauty, mainly due to the pleasant contrast between the red-pink of the sandstone (sometimes purple) and the green of the pines.

The red sandstone from the Lower Triassic (Buntsandstein) is known in the Sierra de Albarracín by the name of the rodeno‘; it is characterised by its siliceous content and the fact that it was formed by sedimentation in a highly arid continental environment, presenting crossed stratifications, which form a thick rocky mass. Of particular note in the geomorphological landscape is the inclination of the strata (10-12° to the west) and the escarpments on the Cabrerizo ravine, which cuts across these formations. In the middle course of this stream, on its left bank, limestone and dolomites from the Middle Triassic (Muschelkalk) emerge, of marine origin and in whitish tones. Coming by road, about 2 km from Albarracín, we will find a rubble dump to our left, next to a set of straw lofts, which is called “El Santo”. From there and approaching the escarpment, a general panorama of the Triassic materials of the Sierra de Albarracín can be observed: the sandstones stand out thanks to their vinous or blue colour due to lichens, in front of a strong fracturing and dip to the S.W. Their morphologies in visors, rounded shapes, towers, uneven and displaced blocks are typical, on the erosion blocks they have created pilancones or gnammas (small pots) and on the front of the blocks there are tafoni (with the appearance of honeycomb). At our feet is Muschelkalk limestone, typical of a marine environment, in whitish and grey tones, which features the differential erosion of the marly levels, resulting in small ridges and shelters. In the background and to the left, as well as behind us, there are materials from the Upper Triassic or Keuper, made up of marl and versicolour gypsum (pink-toned gypsum with which the city was built), which contain abundant Compostela hyacinth. On the Keuper are the limestone and dolomites of the Lías (Rethian), which touch it through a fault.

On the walk inside the Park we will be able to observe, in more detail, the gnammas, tafoni, narrow alleys and corridors between long cone-shaped blocks, cross stratification, differential erosion and the formation of basal shelters, which were used by prehistoric man as a medium for his paintings.

The typical vegetation of this siliceous landscape is dominated by the Rodeno pine or “Pinus pinaster”, used for the production of resin until a few years ago, characterised by its medium height, large cones and thick and rough bark. The undergrowth that accompanies it is very xerophytic: rockrose, gorse, blackberry, some “quercus” (shrubby holm oak), and in the shady areas and wetlands, such as the Reguero ravine, poplars, fruit trees, a greater percentage of “quercus” and the presence of some specimens of black pine that are taller, better bearing, greyer, with thinner bark and smaller cones.

On the limestone there are repopulations of pines, Scots juniper, junipers, at the top creeping junipers and especially gorse, which is typical of very poor and dry soils and which takes advantage of abandoned farming plots to spread and create small impassable forests, due to the decrease in shepherding and the abandonment of the fields.

Under this pine forest you can find milk caps (Lactarius sanguifluus and Lactarius deliciosus), which is yet another attraction of the Park; however, if we forage for mushrooms, we must be respectful of the litter layer, which is very important for the biological self-regulation of this forest.

Routes with Rock Art

In order to visit the Rodeno rock art complex in the Albarracín Cultural Park, the different routes have been marked with coloured arrows, as can be seen on the general panel next to the information centre; thus, the Cabrerizo route is orange, the Navazo area red, Cocinilla del Obispo blue, Arrastradero green and Doña Clotilde yellow.

a) Cabrerizo Spring

Four hundred metres before reaching the Information Centre we will see the signposts on the road, indicating the turn to the left, where we can park. In front of us a channel opens between the rocks, where there is a long flight of stairs that makes it easier for us to descend to the bottom of the ravine. A few metres below, there is a small viewpoint that is worth a stop, as it makes it easier for us to better understand the geomorphology and vegetation of this alley that is the Cabrerizo or Reguero ravine. Strong escarpments, pines, holm oaks and oaks that rise from the cracks in the rock walls, defying gravity, slopes covered with pine trees, the bottom of a ravine once cultivated, now abandoned, the humid vegetation in the background: brambles, holm oaks and oaks on gradients, meadow… It all makes for an impressive scene.

Once the descent is over, to our left is the Cabrerizo Spring, with healthy,fresh water, from which the stream originates. Downstream we see the resin pines, the humid vegetation and the curious shaping caused by fluvial erosion. Any fishing in this stream is prohibited and will be prosecuted. The route that leads us to the shelter is conveniently signposted to its door. Inside, we can see the only two examples of naturalistic engravings in the Park and the only examples we know of engravings free of painting within the rock art of eastern Spain.

On the right there is an equine animal (horse or donkey), which was identified as a hemione (wild donkey that was an ancestor of today’s donkeys), over 50 cm long, made with a thick, deep and wide line; note its long tail, as well as its stylised neck and head. At the other end of the shelter there is a small deer made with a soft V-shaped incision.

b) Navazo Area

The red arrows will lead us to the shelters of: Prado de los Toricos del Navazo (discovered in 1892), Tío Campano and Lázaro. To access this area, we will take the wide path that leads north from the general sign panel, until we reach the mouth of a steep ravine, where another general sign indicates the route to follow for each of the three shelters.

The shelter of “Los Toricos del Prado del Navazo” stands out thanks to its enormous white bulls, which from the edges fix their gaze on the centre of the composition. The white colour is almost exclusive to this area and the naturalism of these figures has made prehistorians suspect that they are very old, sometimes even being dated to the Paleolithic era. In the centre, note the hidden archer taking advantage of a crack in the wall, the perfection of the profile of the great bulls, their horns, snouts and hooves. The drawing is perfect. A superposition in the central left area reveals a small, naturalistic black bull, related to an archer of the same colour, who shoots arrows at it.

The Tío Campano shelter stands out for the presence of two deer with a slender body and schematic antlers, and in the centre there is an equine creature with oblique legs, offering resistance to a force that pulls its nose forward. Maybe it is a domestication scene?

The Lázaro shelter, one of the most recent discoveries in the area, presents a fight scene between a man (well drawn), who could be carrying a mace in his right hand, and another roughly made man who is shooting arrows at him. Above, a squatting archer is aiming at a bovine creature with bent legs, and on the far right, there is a threadlike anthropomorph. For this fight scene, a tafoni (concavity produced by erosion on a sandstone rock wall) was chosen, with the intention of framing the scene.

c) Cocinilla del Obispo

A shelter that became known under the wrong name: Callejón del Plou, a name by which no one knows it in the town, and for this reason the researchers decided to once again call it Cocinilla del Obispo, to avoid confusion.

This route of blue arrows leads us only to this shelter. As in Los Toricos del Prado del Navazo, large white bulls also stand out here, sometimes repainted in red or black, and up to three superpositions can be observed, presenting a size that on two occasions exceeds one meter in length. In the centre there is a rampant bull, which stands on its two hind legs; it is a unique example. The style, theme, as well as the perfection in the details, have always made scholars relate it to the Los Toricos del Prado del Navazo shelter, and even suggest similarly ancient dating.

From here we can access the Arrastradero area via a recently built and signposted path, or return to the information centre and pick up the green arrows from there.

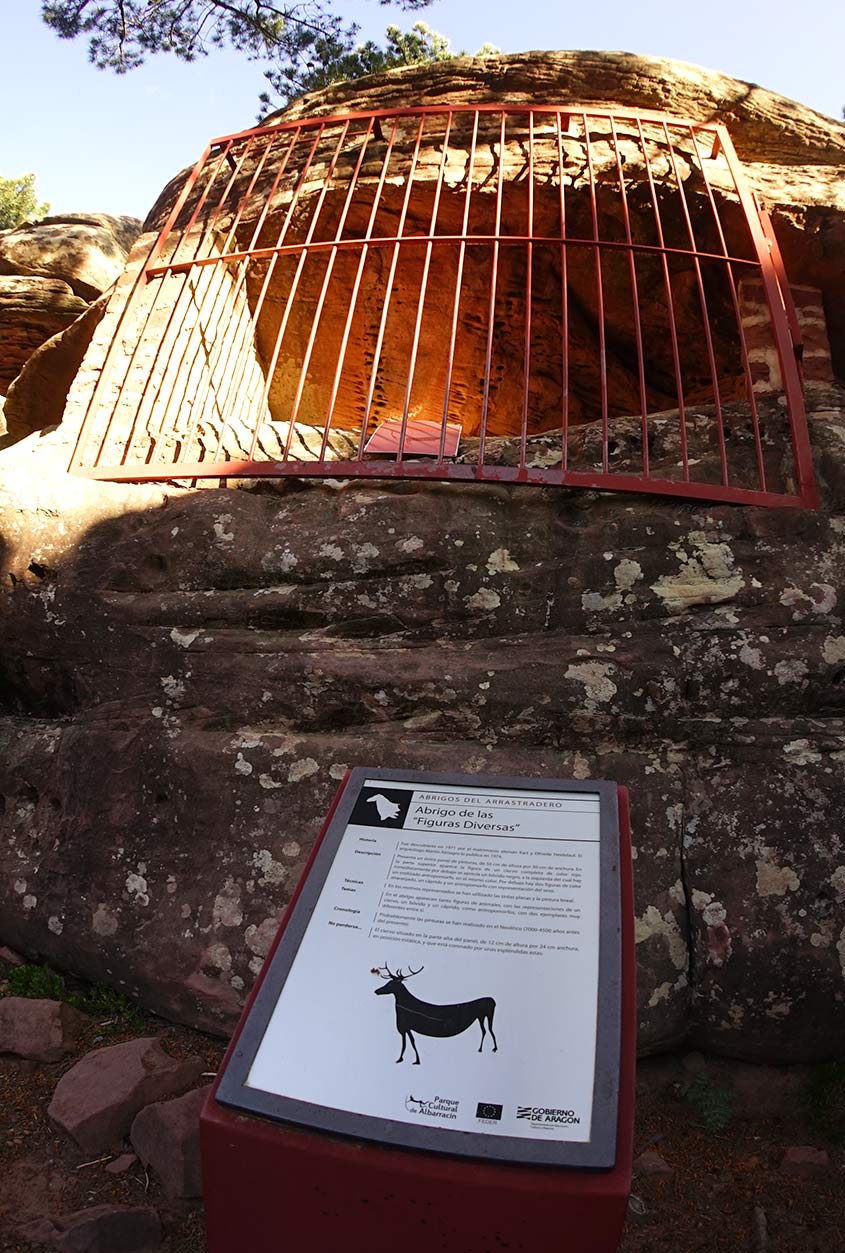

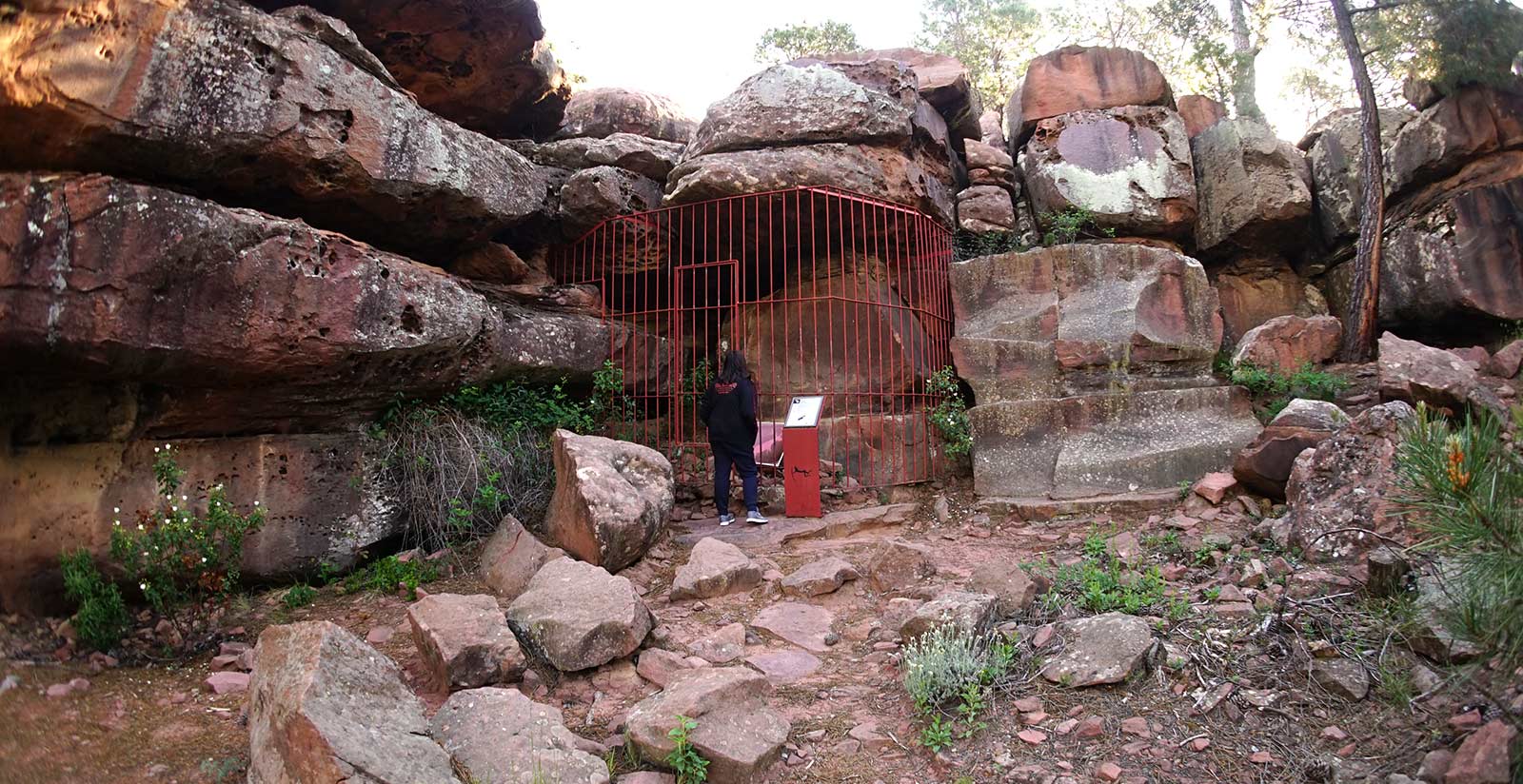

d) Arrastradero Area

Marked by green arrows, we can access this area either from the Cocinilla del Obispo shelter or from the Information Centre.

First, we find the Figuras Diversas shelter, which receives this name precisely due to the variety of figures it contains. There is a perfectly executed naturalistic deer, in red, a black bull and anthropomorphic figures in red and black; this variety prevents us from understanding the meaning and nature of this representation.

Right next door is the El Ciervo shelter, where at least one whole deer can be seen, not without difficulty, and there is another almost whole one and several figures that have been poorly preserved, all in red. This shelter was almost destroyed by operation of the sandstone quarry that was built above and below it.

The green arrows now lead us to one of the most beautiful, rare, complex shelters, with the largest number of figures and the most difficult ones to observe.

It is the Medio Caballo shelter. Until its discovery, it was thought that the presence of the horse in the rock art of the Sierra de Albarracín was insignificant. Several horses were presented with its publication and now, with the revision carried out, there are more than twelve known horses in this shelter. The rarity of this shelter also lies in that the vast majority of the figures are on its ceiling, which is a rare occurrence within Levantine rock art. On the ground we find circles engraved by the tapping technique, and on the front of the shelter we find figures on each of the faces of the sandstone blocks, which makes it difficult to understand the message.

From outside the protective bars, we cannot see the set below on the left, made up of a horse and two indeterminate quadrupeds discovered when reviewing the sketch. It is also impossible for us to observe panel II, because the figures are on the ceiling, made up of four equines of different sizes, which are looking to the right, with figures 7 and 9 in a perfect naturalistic style.

From the outside we can see two black bulls facing each other on panel III. Both are painted in great detail (hooves, tail, horns), and two bull heads can be seen in figure 5. Is this superimposition, or repainting? The body of the primitive bull is only partly preserved, which forces us to consider the reason behind this act and its meaning: to rejuvenate the idea represented, hide the image or concept represented, or simply coincidence or correction. Panel IV reproduces the figure of a beautiful horse, which when discovered was only half observed, hence the name of the shelter; but as can be verified, it is whole, although its hindquarters are very poorly preserved, and can hardly be seen.

Panel V is the roof of the small cave that we have to our left, which can only be seen from the inside and lying on the ground, so a visit with the guard is essential for its observation. With the recent revision of its sketching we have finally been able to complete it, since to date it had been divided. The scene is made up of at least three archers running to the right, bows drawn, to shoot; next to them is possibly a woman with long skirts (figure 19). A group made up of two goats and several horses are heading towards them. All this represents a typical hunting scene, within the purest Levantine art. On the right and within this panel there is a curious scene made up of six horses that whose attention is focused on a large equine creature with a large belly, under which there is a foal. Is it a newborn? Perhaps we are before the representation of a mare in foal? Another figure with a bulging belly is observed next to her. Is she pregnant?

The wall of this low ceiling presents us with a composition of deer that has deteriorated greatly; they look like does that are facing a central area: two to the right, two to the left. We will highlight the only one that is fully represented: is it perhaps drinking or eating? The position of the legs and neck seems to suggest so.

Finally, in the continuation of the ceiling, where we saw the scenes of horses, we can see some figures in an orange colour, which earned them the name of “Yellow Figures”; they were considered until recently to be an independent shelter, as they were separated by the wall built to protect the paintings of the Medio Caballo shelter. Now, with the removal of the wall, it can be clearly seen that they are part of the same shelter, so the “Yellow Figures” shelter name should be abandoned so as not to lead to confusion. This panel VII represents six anthropomorphs (figures in the form of men), painted schematically: one line for the body, another for the arms and two for the legs.

Continuing on our way, we arrive at the Dos Caballos shelter. In the centre there is a rough medium-sized horse, where we can see that the head was repainted, but in a different position: while the first is raised, the second looks down; to its left there are various light-coloured lines, one of which could be an animal’s back, and the other two seem to be poorly preserved schematic figures. At the feet and to the right is a rough horse in a dark red colour, which seems to be related to a human figure, linked to it by a line that is coming out of its chest.

Above this shelter, a black bull in a very good naturalist style has been located in a small cave, so lost and poorly preserved that it cannot be visited by non-specialists, so access is not recommended, unless it is of special interest, in which case you should contact the guard or CEARA.

The arrows finally lead us to the El Arquero de los Callejones Cerrados shelter, presided over by the figure of an archer lying down, ready to shoot, which has been taken as the logo and representative figure of the Cultural Park and CEARA. Observe the care in his feet, the headdress or cap, the perfection in the drawing of his muscles and his pendulous male member. All the way to the left there is a line of colour with multiple interpretations.

When reviewing this shelter, twelve new figures in white have been located; their state of conservation and the type of pigment used make these figures almost imperceptible to the human eye, except when they are observed under artificial light. We highlight from this group a large bull with lyriform horns, an equine creature with a well drawn head, two female figures and an archer similar to the one described in above, all of them painted in white. In the vicinity of this shelter you can visit the Cultural Park’s botanical garden, currently under construction, which is endowed with the most representative plants and trees of the ecosystem.

e) Doña Clotilde Area

Back on the paved road, all that remains is to follow the yellow arrows to reach another shelter, no less important or complex than those seen so far, the shelter or Cave of Doña Clotilde.

The shelter is presided over by a scene which is seen to portray the domestication of a horse, in which an archer with coarse features pulls an equine creature of the same style through a branch or other element that comes from the horse’s nose. Below them, there is a group of archers in the shape of a “T”, with a curious headdress in the form of a “montera” (traditional bullfighter’s cap). Next to them is one of the few plant representations of Levantine rock art, identified by some as a pine tree, but which could be any shrub or tree, whose roots can also be seen.

Finally, we highlight various figures painted in light red or orange colours, within the purest schematic style, reminiscent of anchors and snakes; these drawings cannot be considered Levantine rock art, as they portray another conception of the world and another type of culture and people. These are the most modern representations found in the Cultural Park, which are usually attributed to the Bronze Age culture, and specifically to metallurgical prospectors (people who migrated from the coast toward the interior of the peninsula in search of copper around 2000-1500 BC), a fact that is demonstrated in the Park by the presence of a copper mine attributed to the Bell Beaker culture.

Lifestyles

An important aspect that we must not forget within the Albarracín Cultural Park is the study and diffusion of the ways of life that have allowed the landscape and rock art to be preserved until today, with hardly any variations or aggressions.

Since prehistoric times, hunting and gathering have been common practices within this Park. Neolithic innovations would bring with them the beginning of agricultural practices (Pajarejo Shelter), domestication (Doña Clotilde Cave and Tío Campano Shelter) and grazing. In cultivation, grasses would predominate (plants with grain spikes: oats, barley, wheat etc.); in gathering, fruits from shrubs and acorns; in hunting, goat and deer; and in grazing, the ovicaprids (name given to the common trunk of sheep and goats). This data extrapolated to the Albarracín Cultural Park is confirmed in archaeological sites close to the area and periods under study, which we hope will be confirmed with the excavations we are carrying out. It is curious to note that the animals represented in the shelters do not concur, in percentage and species, with those found in the shelter excavations, which makes us think that these paintings, far from being a representation mimicking ordinary life, are charged with a symbolism that prehistorians are still trying to decipher.

Grazing has been the most common economic practice in the Sierra de Albarracín to the present day. This economic practice and the harsh, cold winters have always forced mountain dwellers to practise transhumance. Perhaps this was the cause of contact with the world of the eastern peninsula, for which it was necessary to create a highly complex system of livestock roads, which would be confirmed and protected centuries later with the Mesta, to which the Community of Albarracín belonged.

Deforestation is essential for agricultural practices, forcing the use of specialised tools, already known since prehistoric times (polished axes), with which the forests would be felled. The clearings in the forest and the plots that are still cultivated today are likely remains of these practices. The contribution of sediments by the ravines and the construction of terraces and fences in the Cabrerizo ravine would facilitate the deposition of alluvial soils of great agricultural quality. In the upper area, outside the ravine, you can currently see cereal farms, some abandoned, which contrast with the irrigated cultivation in the area of La Rabita and Cabrerizo, where the quality of the soil is better, as well as the possibility of irrigation through the use of regulating pools.

The fruit trees and pear in particular brought international fame to this stream, as pears from the Reguero won several international quality awards. Today many pear trees have been uprooted, becoming a residual crop. The Cabrerizo or Reguero orchards, impossible to mechanise, have been abandoned to pasture or have been turned into poplar plantations, with only those closest to Albarracín being cultivated.

From the beginning to the middle of the 20th century, extracting resin from the Rodeno pine was a habitual way of life in this area, which required abundant labour; because of the need to live in the vicinity of the work site, this led to the emergence of a peculiar way of life and several scattered population centres, the most important of which was Casillas de Bezas (current Albarracín neighbourhood); sheds, resin collection huts, trees opened with a hook, pots to collect the resin, etc. can still be seen today.

The hunting of fox, wild boar, rabbit, partridge, and sporadically deer and roe deer, is a common practice within the reserves, for which one must have the respective licences and permits.

A modern way of life that is experiencing a boom is the exploitation of resources generated by tourism, for which a high-quality campsite is being built and, hopefully, nature classrooms will soon be created.

Constructions of Interest

Sheds or shelters

These are common constructions within the Barranco del Cabrerizo or Reguero, as well as the terraces of the Masada de la Rábita or Rabita. They have a square or rectangular plan of 4 to 6 m2; only rarely do they have a ground floor and a raised floor that is used as a loft. The roofs are one slope, rarely two, and the interior is illuminated by tiny windows and a door.

They have stone walls or a stone plinth and a mud and earth plaster wall with half-timbering, a dirt floor and a wooden door, primitive elements that allow for an elementary construction for a specific purpose.

In the modern sociocultural environment, they have been misused, as people have attempted to turn these shelters into small country houses, an example that we can see in the vicinity of the Masía de la Rábita. This bad example cannot be repeated any more, since the Subsidiary Regulations of the Municipality of Albarracín have protected the Park since 1991 through a Special Plan that prohibits these renovations and changes of use.

Regulating Pools

As indicated above, the Reguero or Cabrerizo, even with its minimal contribution of water, allows for the irrigation of the small orchards emerging from the terraces.

The low flow of water from the Reguero forced man to establish a supposed irrigation regulation, which required agreeing on the days and hours of water intake for irrigation.

The impossibility of building dams means the regulating pool system is the most suitable for irrigation. From the water course, with some simple stones, clay and tarrancleras (wooden gates), the flow is diverted towards small irrigation canals or “regueros” that lead the water to different types of regulating pools. They range from pools made of stone and plastered with lime, down to the simplest holes, dug in the ground, with a proportional capacity to the orchard that needs to be irrigated, in such a way that one filling serves to water the orchard once. Once these tanks are full, which sometimes took more than one night, the lower gate is opened, from which the water flows to the orchard.

Straw lofts and threshing floors

The straw lofts and threshing floors of the Albarracín Cultural Park are outside irrigated farms, which is why we observe them mainly in the limestone areas and sometimes in the sandstone, but always related to large areas of dry land cultivation.

In the vicinity of the Albarracín Complex we can observe 3 isolated groups: El Santo, Losilla Baja and Loma Alta. These groups of straw lofts and threshing floors are not related to any nearby dwelling, since their operators live in Albarracín and do the pre-treatment in the field, unlike the farmers who live where they farm and work, as we will see.

We will see some straw lofts and threshing floors that are isolated, but what is striking is those that are grouped together, which makes them ideal to visit, although they require urgent restoration, such as Losilla Baja, next to the esplanade where the Fuente del Cabrerizo shelter sign is located.

For its construction, a group of sandstone blocks has been used as walls; the supports for the beams of the roofs and the second floor are excavated into them, and even the corridors between blocks are sometimes used to create animal enclosures or farrowing pens. That is to say, the constructions are totally and absolutely adapted to the environment.

Sheepfolds or farrowing pens

Sheepfolds or farrowing pens are common within the Rodeno de Albarracín complex, which testify to the area’s livestock raising tradition. Sometimes they appear isolated in the middle of the field, oriented towards the sun and close to grassy areas.

Stone-wall pens have a rectangular floor plan and a height of almost 2 m, topped by an accumulation of dry brambles and gorse. Inside the enclosure and taking advantage of the three walls, a shed is built by means of a mother beam, supported on a central pillar on which stripped pine beams rest on a single slope, attached with boards and on them tiles with mud or a roof made of branches. They can usually be found in places that take advantage of natural shelters or the elegant structures that comprise the corridors between sandstone blocks. The use of shelters as sheepfolds has sometimes led to the destruction or smoking of stone paintings. Examples of shelters with rock art that have been used as sheepfolds include the Fuente del Cabrerizo, Cerrada del Tío Jorge and Paridera de Enmedio shelters; on other occasions we find them near one another: the Tío Campano shelter, next to the Enmedio farrowing pen.

At the risk of being repetitive, it does not hurt in this last section to review the restrictions, which unfortunately with the increase in tourism, are increasingly overlooked.

Everything that common sense and current legislation restricts is prohibited: littering, throwing wrappers or paper on the ground, throwing stones at signs, breaking signs, breaking railing, writing on signs… Even if it seems unbelievable to the reader, these are the most common occurrences, and administrative or criminal sanctions in each case will be applied according to the seriousness and damages produced.

Vehicles are prohibited, except on tarmacked roads.

Vehicles may only be parked in the parking area.

Throwing objects at the rock paintings is forbidden.

Wetting the rock paintings with any liquid, including water, is forbidden. They all wash off, deteriorate and lead to the loss of this important heritage. The destruction of Spanish historical heritage is punishable and prosecuted as a criminal offence.

Unless expressly authorised, collecting plant species or cutting down trees is prohibited.

Camping is prohibited, except in the area reserved for this purpose.

Hunting or fishing is prohibited, unless expressly authorised.

Fuente: Octavio Collado Villalba

More information

Complementary information for your visit to Albarracín